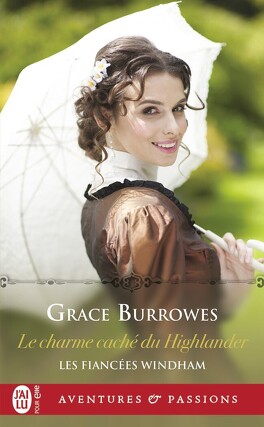

Ajouter un extrait

Liste des extraits

Extrait offert par Grace Burrowes

(Source : http://graceburrowes.com)

Miss Megan Windham is falling in love with Hamish MacHugh, the newly title Duke of Murdoch. Megan’s cousins, however, Westhaven, St. Just, and Valentine, will take an interest in her situation that closely resembles, well, meddling…

Gayle Windham, Earl of Westhaven was too self-disciplined to glance at the clock more than once every five minutes, but he could see the shadow of an oak limb start its afternoon march up the wall of his study. The remains of a beef sandwich sat on a tray at his elbow, and soon his youngest child would go down for a nap.

Westhaven brought his attention back to the pleasurable business of reviewing household expenses, though Anna’s accounting was meticulous. He obliged his countess’s request to look over the books because of the small insights he gained regarding his family.

They were using fewer candles, testament to Spring’s arrival and longer hours of daylight.

The wine cellar had required some attention, another harbinger of the upcoming social season.

Anna had spent a bit much on Cousin Megan’s birthday gift, but a music box was a perfect choice for Megan.

“You haven’t moved in all the months I’ve been gone,” said a humorous baritone. “You’re like one of those statues, standing guard through the seasons, until some obliging brother comes along to demand that you join him in the park for a hack on a pretty afternoon.”

Home safe. Devlin St. Just’s dark hair was tousled, his clothes wrinkled, his boots dusty, but he was once again, home safe.

The words were an irrational product of Westhaven’s memory, for his mind produced them every time he saw his older half-brother after a prolonged absence. Westhaven crossed the study with more swiftness than dignity, hand extended toward his brother.

“Good God, you stink, St. Just, and the dust of the road will befoul my carpets wherever you pass.”

St. Just took Westhaven’s proffered hand and yanked the earl close enough for a quick, back-thumping hug.

“I stink, you scold. Give a man a brandy while he befouls your carpets, and good day to you too.”

Westhaven obliged, mostly to have something to do other than gawk at his brother. Yorkshire was too far away, the winters were too long and miserable, and St. Just visited too infrequently, but every time he did visit, he seemed…. Lighter. More settled, more at peace.

And if ever a man was happy to smell of horse, it was St. Just.

“I have whisky,” Westhaven said. “I’m told the barbarians to the north favor it over brandy.”

“If you had decent whisky, I might consider it, but you’re a brandy snob, so brandy it is. How are the children?”

Thank God for the topic of children, which allowed two men who’d missed each other terribly to avoid admitting as much.

“The children are noisy, expensive, and a trial to any parent’s nerves. Our parents come by, dispensing falsehoods regarding my own youth along with a surfeit of sweets. Then their graces parents swan off, leaving my kingdom in utter disarray.”

Westhaven passed St. Just a healthy portion of spirits, though being St. Just, he waited until Westhaven was holding his own glass.

“To kingdoms in disarray,” St. Just said, touching his glass to Westhaven’s. “Try uprooting your womenfolk and dragging them hundreds of miles on the king’s highway. Your realm shrinks to the proportions of one very unforgiving saddle. Rather like being on campaign.”

St. Just could do this now—make passing, halfway humorous references to his army days. For the first two years after he’d mustered out, he’d been unable to remain sober during a thunderstorm.

“Her ladyship is well?” Westhaven asked.

Back to top ↑ trouble_450x2

“My Emmie is a saint,” St. Just countered, taking the seat behind Westhaven’s desk. “If you die, I want this chair.”

“Spare me your military humor. If I die, you and Valentine are guardians of my children.”

A dusty boot thunked onto the corner of Westhaven’s antique desk, the same corner upon which Westhaven’s own, much less dusty boots, were often propped, provided the door was closed.

“Val and I? You didn’t make Moreland their guardian?”

“His grace will intrude, meddle, advise, maneuver, interfere, and otherwise orchestrate matters as he sees fit, abetted by our lovely mother in all particulars. Putting legal authority over the children in your hands was my pathetic gesture toward thwarting the ducal schemes. You will, of course, oblige my guilt over this presumption by giving me a similar role in the lives of your children.”

St. Just closed his eyes. He was a handsome fellow, handsomer for having regained some of the muscle he’d had as a younger man.

“I can hear His Grace’s voice when you start braying about what I shall oblige and troweling on verbs in sextuplicate.”

“Is that a word?”

“Trowel, yes, a humble verb. Probably Saxon rather than Roman in origin.”

Westhaven pretended to savor his brandy, when he was in truth savoring the fact that his older brother would—in all his dirt—come to Westhaven’s establishment before calling upon the ducal household.

“Where is your countess, St. Just? She’s usually affixed to your side like a very pretty cocklebur.”

“Where’s yours?” St. Just retorted. “I dropped Emmie and the girls off at Louisa and Joseph’s, though I’m to collect them—”

The door opened, and a handsome dark-haired fellow sauntered in, Westhaven’s butler looking choleric on his heels.

“I come seeking asylum,” Lord Valentine said.

St. Just was on his feet and across the room almost before Val had finished speaking. The oldest and youngest Windham brothers bore a resemblance, both dark-haired, and both carrying with them a physical sense of passion. Valentine loved his music, St. Just his horses, and yet the brothers were alike in a way Westhaven appreciated more than he envied—mostly.

“You come seeking my good brandy,” Westhaven said, when Val had been properly embraced and thumped by St. Just. “Here.”

He passed Valentine his own portion and poured another for himself.

“We were about to toast our happy state of marital pandemonium,” St. Just said. “Or so Westhaven thinks. I’m in truth fortifying myself to storm the ducal citadel.”

Valentine took his turn in Westhaven’s chair. “I’d blow retreat if I were you.”

Westhaven took one of the chairs across from the desk. “What have their graces done now?”

Valentine preferred to prop his boots—moderately dusty—on the opposite corner from his brothers. This put the sunlight over Val’s left shoulder.

None of the brothers had any gray hairs yet, something of a competition in Westhaven’s mind, though he wasn’t sure whether first past the post would be the winner or the loser. They were only in their thirties, but they were all fathers of small children—small Windham children.

“His grace is sending Uncle Tony and Aunt Gladys on maneuvers in Wales directly after the ball,” Valentine said, “while her grace will snatch up our cousins, doubtless in anticipation of some matchmaking.”

They had four female cousins: Beth, Charlotte, Megan, and Anwen. They were lovely young women, red-haired, intelligent, and well dowered, but they were Windhams, and thus in no hurry to marry.

A situation the duchess sought to remedy.

Back to top ↑ trouble_450x2

“So that’s why Megan was particularly effusive in her suggestions that I come south,” St. Just mused, opening a japanned box on the mantel. “Emmie said something untoward was afoot.”

A piece of marzipan disappeared down St. Just’s maw.

“Goes well with brandy,” he said, offering the box to Val, who took two. “Westhaven?”

“How generous of you, St. Just.” He took three, though the desk held another box, which his brothers might not find. His children hadn’t.

Yet.

“Beth and Megan have both been through enough seasons to know how to repel boarders,” Westhaven said.

“I wondered what their graces would do when they got us all married off,” Valentine mused, brandy glass held just so before his elegant mouth. “I thought they’d turn to charitable works, a rest between rounds until the grandchildren grew older.”

He tossed a bit of marizipan in the air and caught it in his mouth, just he would have twenty years earlier, and the sight pleased Westhaven in a way that he might admit when all of his hair was gray.

“Beth is weakening,” Westhaven said. “She’s become prone to megrims, sore knees, a touch of a sniffle. Anna and I do what we can, but the children keep us busy, as does the business of the dukedom.”

“And we all thank God you’ve taken that mare’s nest in hand,” St. Just said, lifting his glass. “How do matters stand, if you don’t mind a soldier’s blunt speech?”

“We’re firmly on our financial feet,” Westhaven said. “Oddly enough, Moreland is in part responsible. Because he didn’t bother with wartime speculation, when the Corsican was finally buttoned up, once for all, our finances went through none of the difficult adjustments many others are still reeling from.”

“If you ever do reel,” Valentine said, “you will apply to me for assistance, or I’ll thrash you silly, Westhaven.”

“And to me,” St. Just said. “Or I’ll finish the job Valentine starts.”

“My thanks for your violent threats,” Westhaven said, hiding a smile behind his brandy glass. “Do I take it you fellows would rather establish yourselves under my roof than at the ducal mansion?”

Valentine and St. Just exchanged a look that put Westhaven in mind of their parents.

“If we’re to coordinate the defense of our unmarried lady cousins,” St. Just said, “then it makes sense we’d impose on your hospitality, Westhaven.”

“We’re agreed then,” Valentine said, raiding the tin once more. “Ellen will be relieved. Noise and excitement aren’t good for a woman in her condition, and this place will be only half as uproarious as Moreland House.”

“We must think of our cousins,” St. Just replied. “The combined might of the duke and duchess of Moreland are arrayed against the freedom of four dear and determined young ladies who will not surrender their spinsterhood lightly.”

“Nor should they,” Westhaven murmured, replacing the lid on the tin, only for St. Just to pry it off. “We had the right to choose as we saw fit, as did our sisters. You’d think their graces would have learned their lessons by now.”

A knock sounded on the door. Valentine sat up straight, St. Just hopped to his feet to replace the tin on the mantel, and was standing, hands behind his back, when Westhaven bid the next caller to enter.

“His Grace, the Duke of Moreland, my lords,” the butler announced.

In the next instant, Percival Windham stepped nimbly around the butler and marched into the study.

“Well done, well done. My boys have called a meeting of the Windham subcommittee on the disgraceful surplus of spinsters soon to be gathered into her grace’s care. St. Just, you’re looking well. Valentine, when did you take to wearing jam on your linen?”

Moreland swiped the tin off the mantel, opened it, took the chair next to Westhaven and set the box in the middle of the desk.

“I’m listening, gentlemen,” the duke said, popping a sweet into his mouth. “Unless you want to see your old papa lose what few wits he has remaining after raising you lot, you will please tell me how to get your cousins married off post haste. The duchess has spoken, and we are her slaves in all things, are we not?”

Back to top ↑ trouble_450x2

Westhaven reached for a piece of marzipan, St. Just fetched the brandy decanter, and Valentine sent the butler for sandwiches, because what on earth could any of them say to a ducal proclamation such as that?

Read on for another scene from The Trouble With Dukes…

Megan Windham has recruited her cousins to assist her in teaching Hamish MacHugh, the new Duke of Murdoch, how to waltz. When Megan switched Gaelic, and Hamish stumbled, and fell… in love.

Hamish would fight across Spain, scale the mountains, and march through the whole of France all over again for a waltz like the one he was sharing with Megan Windham.

He danced with the same passionate abandon formerly reserved for when the swords were crossed after the fourth dram of whisky, and the camp followers had acquired the airs and graces of every soldier’s dreams.

Megan Windham beamed up at him, her hand clasped in his, her rhythm faultless, her form starlight in his arms.

When the music came to a final, sighing cadence, Hamish’s heart sighed along with it.

“My thanks for a delightful waltz,” he said, as Miss Megan sank into a deep curtsy. She kept hold of Hamish’s hand as he drew her to her feet and bowed.

“The pleasure was entirely mine, your grace.”

While the sorrow was Hamish’s. To her, this was just another waltz, a charity bestowed on a reluctant recruit to the ranks of the aristocracy.

To Hamish it had been—

“Now you lead her from the dance floor,” the big cousin barked. “Parade march will do, her hand resting on yours.”

On general principles, Hamish stood his ground. This fellow had begun to look and sound familiar, and one thing was certain: Hamish had the highest ranking title in the room.

“You served on the Peninsula?” Hamish asked.

Megan’s cousin spoke with an air of command, and he had the watchful eyes of the career soldier. Hamish put his age at about mid-thirties, and his weight about fourteen stone barefoot and stripped for a fight. His waltzing had been worthy of a direct report to Old Hooky himself, his scowl was worthy of a captain, possibly a major.

“You behold Colonel Lord Rosecroft,” Miss Megan said, patting the fellow’s cheek. “Cousin Devlin is quite fierce, but he has to be. He’s the father of two daughters and counting, and the oldest of ten siblings. Her grace contends that he joined up in search of a more peaceful existence.”

Rosecroft shot Hamish a glance known to veterans the world over. Let her make light of me, that look said. Let her make a joke of the endless horrors. We fought so that our womenfolk could pat our cheeks and jest at our nightmares. They remained at home, praying for us year after year, so that some of us could survive to make light of their nightmares too.

Miss Megan tugged at Hamish’s hand. “Now you return me to my chaperone or help me find my next partner, the same as any other dance. We make small talk, greet the other guests, and look quite convivial.”

“That’s three impossibilities you’ve set before me, Miss Meggie.”

Hamish had amused her, simply by speaking the truth. “I saw you smile, your grace,” she said, leading Hamish over to the piano. “Your charm might be latent, but it’s genuine.”

He leaned closer. “I won’t know your next partner from the crossing sweeper, I have no patience with small talk, and looking convivial is an impossibility when you’re known as the Duke of Mur—”

“A gentleman never argues with a lady,” the colonel observed, hands behind his back, two paces to Miss Megan’s right. He bore a resemblance to Moreland, in his posture and about the jaw, and yet, he was apparently not the heir.

“Does a gentleman lie to a lady, Rosebud? My sisters will tell you I can’t keep social niceties straight, I lack familiarity with those of your ilk, and I’ve no gift for idle chit-chat.”

“None at all,” Edana said.

“He’s awful,” Rhona added, russet curls bobbing, she nodded so earnestly. “We despair of him, but one can’t instruct a brother when he won’t even try to accept one’s guidance. We tell him to inquire about the weather, and his response is that any woman who can’t notice the weather for herself won’t notice a lack of chatter in a man.”

They meant well, and they were being honest, but a part of Hamish felt as if he’d been knocked on his arse again, kilt flapping for all the world to see.

Back to top ↑ trouble_450x2

“I’ve made the very same point to my countess,” the auburn-haired Earl of Enunciation said. Hamish could not recall his name. “Why must we discuss the weather at tedious length when there’s nothing to be done about it, and its characteristics are abundantly obvious. Better to discuss….”

Edana, Rhona, and Miss Megan regarded him curiously.

“The music,” said Lord Nancy Pants rising from the piano. He was a good-sized fellow, for all his lace, and he had that ducal jaw too. “Ask her if she prefers the violin or the flute, the piano or the harpsichord. Ask her what her favorite dance is, and then ask her why.”

“That is brilliant,” the earl said. “A lady can natter on about why this or why that for hours, and then why not the other.”

“You didn’t unearth that insight on your own,” the colonel interjected. “Ellen put you on to it, and you’re taking the credit.”

Nancy Pants grinned, looking abruptly like Colin—a younger sibling who’d got over on his elders, again.

“Gentlemen, please,” Miss Megan said. “Valentine’s smile presages fisticuffs, and we’ve already obligingly moved the furniture aside. The point of the gathering is not to indulge your juvenile glee in one another’s company, but rather, to make certain that his grace of Murdoch acquits himself well at Aunt Esther’s gathering.”

Three handsome lords looked fleetingly abashed.

Women did this. They wore slippers that could kick a man’s figurative backside with the force of a jackboot. Their verbal kid gloves could slap with the sting of a riding crop, and their scowls could reduce a fellow’s innards to three-day-old neeps and tatties.

To see three English aristocrats so effectively thrashed did a Scottish soldier’s heart good.

“Small talk can be learned,” the ducal heir said, entirely too confidently. “You’re good with languages, Megs. Teach your duke the London ballroom dialect of small talk. If my brothers could learn it, it’s not that difficult.”

“If you hadn’t had my example to follow—” the colonel growled.

“Would you please?” Edana asked. “We’ve tried, but Hamish… he’s stubborn.”

“And slow,” Rhona added. “Not dull, but everything must make sense to him, and that is a challenging undertaking when so much about polite society is for the sake of appearance rather than substance.”

They were being helpful again, drat them both. “I manage well enough in the kirk yard.”

“Church yard,” all three cousins said at once.

“Where I come from, where I am a duke, it’s a kirk yard,” Hamish said. “And to there I will return in short order, the shorter the better.”

Edana’s expression promised Hamish a violent end before he could set a foot on the Great North Road. Rhona looked like she wanted to cry, however, and that… that shamed a man as falling on his arse before English nobility never could.

“Walk in the park,” Lord Twiddly Fingers said. “Tomorrow, if the weather is fair, Megan can join his grace for a walk in the park. Joseph and Louisa are in Town, Evie and Deene, are as well. Take Lady Rhona and Lady Edana walking, Murdoch. Megan will be attended by a pair of brothers-in-law, both of them titled, and you can rehearse your small talk.”

“Excellent tactics,” the colonel muttered.

“Her grace would approve,” the earl said. “I like it. Megan?”

She’d rather be called Meggie by those who cared for her. Hamish would rather sneak off to Scotland that very moment. Hyde Park was a huge place, crammed full of bonnets, parasols, ambushes wearing sprigged muslin, and half-pay peacocks in their regimentals.

Rhona looked at her slippers. Peach-ish today, more expensive idiocy, but studying his sister’s bowed head, Hamish located the reserves of courage necessary to endure another battle.

“If Miss Megan can spare me the time to walk in the park, I would be grateful for her company.”

“Oh, well done, your grace,” she said, smiling at him. Not the great beaming version he’d seen on the dance floor, but a softer, even more beguiling expression that turned her gaze soft and Hamish’s knees to porridge.

Back to top ↑ trouble_450x2

“Two of the clock then,” the earl said. “Assemble here. I’ll make the introductions, and her grace’s ball will be the envy of polite society, as usual.”

Within five minutes, Hamish was bowing over Miss Megan’s hand in parting, though he’d committed himself to tomorrow’s skirmish in defense of MacHugh family pride—or something. The Windham cousins seemed genuinely, if grudgingly, intent on aiding the cause of Hamish’s education, probably for the sake of their own family pride.

And Miss Megan was smiling.

Hamish was so preoccupied with mentally assembling metaphors to describe her smile that he nearly missed the low rumble of the pianist’s voice amid the farewells and parting kisses of the ladies.

“He’s a disaster in plaid,” Lord Nancy Pants muttered.

“He provoked Megan into trotting out her Gaelic,” the colonel added. “Not the done thing.”

Well, no it wasn’t. Falling on one’s arse was not the done thing, arguing with a lady was not the done thing. One ball however, for the sake of Ronnie and Eddie’e pride, one little march about the park, and Hamish could retreat with honor, which sometimes was the done thing.

Hamish got Rhona by one arm, Edana by the other, and hauled them bodily toward the door, which was held open by a fellow in handsome blue livery.

“My thanks for dancing lesson,” Hamish called, because expressing sincere gratitude was also the done thing where he came from. “Until tomorrow.”

Miss Megan waved to him. “Mar sin leibh.” A friendly farewell that fortified a man against coming battles, and provoked both the colonel and the musician to scowling.

And as the liveried fellow closed the door, another snippet of clipped, masculine, aristocratic English came to Hamish’s ears.

“You two give up too easily. I think Murdoch has potential, Rosebud.”

Afficher en entier